The Science Behind Camel Milk in Skincare

Published by Max Silvester – Camelixir

Camel milk has been part of traditional diets across arid regions for centuries. In recent years, researchers have started to look closely at its unique composition to understand whether it might also bring value in modern skincare. This article takes a deep dive into what peer-reviewed science says about camel milk, with a particular focus on dromedary camels from Kenya.

How This Report Was Compiled

We reviewed peer-reviewed literature through PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus. Search terms included camel milk, dromedary milk composition, bioactive proteins, lactoferrin, lactoperoxidase, PGRP, lysozyme, vitamin content, and cosmetic applications. We focused on high-quality compositional studies and reviews; conference abstracts were excluded unless later published in journals.

Key Bioactive Proteins

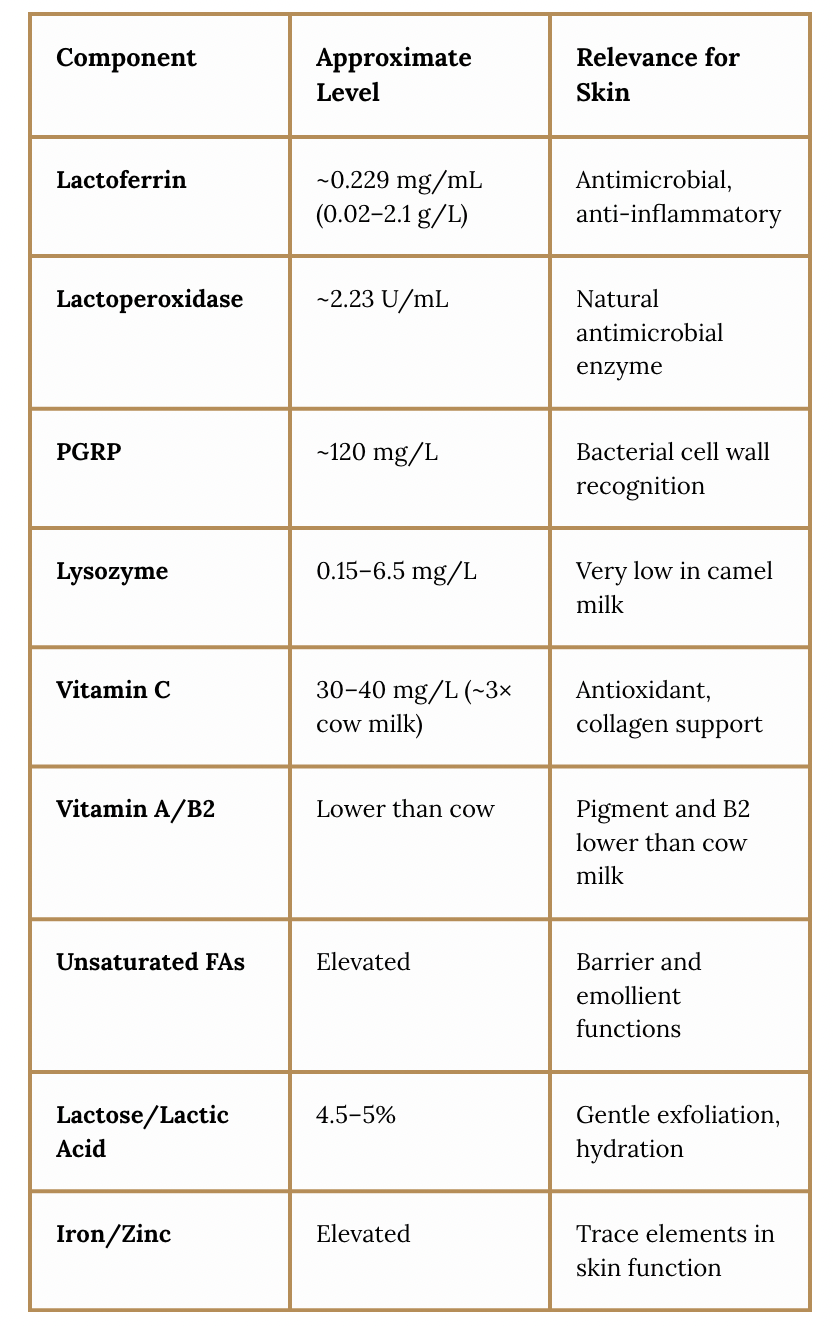

Lactoferrin (Lf): Found at 0.02–2.10 g/L, with typical mature-milk averages of ~0.229 mg/mL (Konuspayeva et al., 2007; Swelum et al., 2021). Lf is known for antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties.

Lactoperoxidase (LPO): Reported activity of ~2.23 U/mL (Singh et al., 2017). This enzyme is part of the natural antimicrobial system but is heat-sensitive (Tayefi-Nasrabadi et al., 2011).

Peptidoglycan Recognition Protein (PGRP): Present at ~120 mg/L, unusually high compared to cow’s milk (Kappeler et al., 2004).

Lysozyme: Very low in camel milk (0.15–6.5 mg/L), compared with donkey milk (~1 g/L) (Derdak et al., 2020).

Immunoglobulins (IgG, IgA, IgM): Strong in colostrum, with lower but measurable levels in mature milk (Swelum et al., 2021).

Fats and Fatty Acids

Camel milk fat makes up about 3–4% of the liquid. Studies show a higher proportion of unsaturated fatty acids (oleic, linoleic, palmitoleic) compared with cow’s milk, which may contribute to skin barrier support and texture (Konuspayeva et al., 2008).

Vitamin and Antioxidant Profile

Vitamin C: Three times higher than in cow’s milk (30–40 mg/L) (Farah & Rüegg, 1992; Swelum et al., 2021).

Vitamin E: Present but at low levels (Bakry et al., 2021).

Vitamin A and Riboflavin (B2): Lower in camel milk than in cow’s milk (Farah & Rüegg, 1992).

Niacin (B3): Higher compared to cow’s milk.

Carbohydrates and Natural Acids

Lactose: Similar to cow’s milk at ~4.5–5% (Swelum et al., 2021).

Lactic acid: Generated through fermentation and classified as an alpha-hydroxy acid (AHA), which supports gentle exfoliation (Oginga et al., 2024).

Minerals

Camel milk often contains more iron and zinc compared with cow’s milk (Swelum et al., 2021). These minerals are largely bound to proteins such as lactoferrin.

How Camel Milk Compares

Cow’s milk: Higher in vitamin A and riboflavin; lower in vitamin C and lactoferrin.

Goat’s milk: Well known for soaps; contains more medium-chain fats but less lactoferrin and LPO.

Donkey’s milk: Very high in lysozyme (~1 g/L), which makes it antimicrobial in a different way than camel milk (Nayak et al., 2020; Derdak et al., 2020).

Kenya’s Place in the Story

Kenya produces over 1 million metric tons of camel milk annually. Beyond food use, there’s growing exploration of its potential in value-added products, including skincare and cosmetics (Oselu et al., 2022).

Quick Reference Table

Why This Matters for Skincare

Taken together, these bioactive proteins, vitamins, minerals, and fatty acids make camel milk a uniquely multifunctional ingredient for skincare. Its lactoferrin, lactoperoxidase, and PGRP provide natural antimicrobial and soothing properties, while its unsaturated fatty acids help strengthen the skin barrier and maintain softness. The high vitamin C content contributes antioxidant protection and supports collagen synthesis, while lactic acid offers gentle exfoliation and hydration. Trace minerals such as zinc and iron further promote skin repair and resilience. This combination of protective, nourishing, and revitalizing elements explains why camel milk is increasingly seen as a valuable addition to modern skincare formulations.

Compliance Note

This article is for informational purposes only. It does not provide formulation or marketing guidance. If camel milk or its derivatives are used in cosmetics, compliance with Kenyan standards (KS EAS 151:2018) and international frameworks (e.g., EU Cosmetics Regulation 1223/2009, FDA Cosmetic Regulations) is required. Claims must remain cosmetic (e.g., “supports skin appearance”) and avoid medical language. A legal review is advised before publication or product marketing.

References

Bakry IA, et al. (2021). Review of camel-milk fat composition. Foods, 10(9):2148. doi:10.3390/foods10092148

Derdak R, et al. (2020). Insights on health and food applications of donkey milk. Foods, 9(9):1302. doi:10.3390/foods9091302

Farah Z & Rüegg M. (1992). The vitamin content of camel milk. Int J Vitam Nutr Res, 62(1):30–33. PMID: 1574695

Konuspayeva G, et al. (2007). Lactoferrin and immunoglobulins in camel milk. J Dairy Sci, 90(1):38–46. doi:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(07)72606-1

Konuspayeva G, et al. (2008). Fatty acids in camel milk. Dairy Sci Technol, 88:327–340. doi:10.1051/dst:2008005

Kappeler S, et al. (2004). Peptidoglycan recognition protein in camel milk. J Dairy Sci, 87(10):3186–3192. doi:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(04)73392-5

Nayak CM, et al. (2020). Donkey milk lysozyme. Int J Food Sci Technol, 55(8):3102–3110. doi:10.1111/ijfs.14575

Oginga E, et al. (2024). Camel milk in soaps/shampoos review. Dermatol Res Pract, Article ID 4846339. doi:10.1155/2024/4846339

Oselu S, et al. (2022). Camel milk industry in Kenya. Int J Food Sci, 2022:1237423. doi:10.1155/2022/1237423

Singh R, Mal G, Kumar D, Patil NV, Pathak KML. (2017). Camel milk: An important natural adjuvant. Agric Res, 6:327–340. doi:10.1007/s40003-017-0284-4

Swelum AA, et al. (2021). Nutritional, antimicrobial and medicinal properties of camel’s milk. Saudi J Biol Sci, 28(5):3126–3136. doi:10.1016/j.sjbs.2021.02.057

Tayefi-Nasrabadi H, et al. (2011). Heat treatment's effect on LPO. Small Rumin Res, 99:187–190. doi:10.1016/j.smallrumres.2011.04.003